When discussing shoulder range of motion norms, we are fundamentally asking: What constitutes a "normal" amount of movement for a healthy shoulder? While traditional academic sources may cite precise figures such as 180° for major movements like flexion and abduction, clinical reality often presents a more varied picture.

Data from population studies indicate that real-world averages in healthy adults are frequently lower than these idealised benchmarks (1). This is not necessarily a sign of pathology but rather a reflection of normal human variation, influenced by factors such as age, gender, and individual anatomy. Understanding these norms is the first step in accurately distinguishing a true functional limitation from what is simply normal for a given individual.

Understanding the Baseline for Shoulder Movement

A healthy shoulder complex is a sophisticated anatomical structure, allowing for the extensive arc of motion required for daily activities—from reaching for an object on a high shelf to participating in athletic endeavours. To quantify this mobility, we measure movement in specific planes.

This process provides a crucial baseline, enabling clinicians to differentiate between normal, healthy variation and a potential indicator of dysfunction. Consequently, assessing a patient against established shoulder range of motion norms is a cornerstone of any upper body physical examination.

The primary movements measured are:

- Flexion: Lifting the arm straight forward and overhead.

- Abduction: Lifting the arm out to the side and overhead.

- External Rotation: With the elbow held at the side, rotating the forearm outward.

- Internal Rotation: Rotating the arm inward, such as when placing a hand behind the back.

Traditional Norms vs. Population Averages

For many years, the values published by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) were considered the standard reference. These guidelines defined a "normal" active shoulder range as 180° for both flexion and abduction, with 90° for external rotation (2). These are the values commonly taught in academic programs.

However, as more population-based research has emerged, it has become evident that the actual averages in healthy adults are often slightly lower than these idealised figures. This distinction is clinically significant. Rigid adherence to older textbook values could lead to the misinterpretation of a healthy shoulder as having a deficit. This is where understanding the difference between a textbook ideal and actual what is normative data becomes critical for accurate assessment.

Quick Reference: Shoulder ROM Norms (AAOS vs. Population Averages)

This table contrasts the traditional AAOS standards with more contemporary, evidence-based population averages, offering a more realistic framework for clinical measurement.

| Movement | Traditional AAOS Norm (2) | Recent Population Average (Approx.) (1) | Primary Muscles Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion | 180° | 150° - 165° | Anterior Deltoid, Pectoralis Major, Coracobrachialis, Biceps |

| Abduction | 180° | 150° - 170° | Middle Deltoid, Supraspinatus |

| External Rotation (arm at side) | 90° | 70° - 90° | Infraspinatus, Teres Minor |

| Internal Rotation (arm at side) | 70° | 60° - 75° | Subscapularis, Teres Major, Latissimus Dorsi, Pectoralis Major |

The AAOS values represent an ideal maximum, while typical findings in an average individual are slightly less. A thorough assessment must therefore extend beyond a single numerical comparison, taking into account the individual's age, activity level, and, critically, symmetry between both shoulders. The complete clinical picture is always more valuable than a simple comparison to an absolute standard.

Standardized Protocols for Measuring Shoulder ROM

To ensure that shoulder range of motion measurements are both accurate and clinically useful, the use of a standardized protocol is essential. Without it, measurements can vary significantly, even when taken by the same clinician on the same day. The primary goal is to isolate the movement of the glenohumeral joint, which requires careful patient positioning and stabilization.

A consistent methodology reduces the variables that can compromise results. For example, a common error is failing to stabilize the scapula. When the scapula moves freely, the trunk and thoracic spine can contribute to the motion, artificially inflating the ROM reading. This leads to inaccurate data and can misguide clinical decisions regarding a patient’s progress or limitations.

Core Principles of Goniometric Measurement

The universal goniometer remains the most common tool for this assessment. Proper use requires aligning its arms with specific anatomical landmarks while the patient is positioned correctly—typically supine (lying on their back) for flexion and abduction to limit compensatory movements from other body parts (3).

Here is a summary of the process for key movements:

- Patient Positioning: The patient should be comfortable, typically lying flat on a firm surface. This step helps stabilize the pelvis and trunk, preventing them from contributing to the arm's movement.

- Scapular Stabilization: Before measurement, gentle pressure should be applied to the scapula, or the patient should be positioned to naturally restrict its movement. This is critical for isolating true glenohumeral joint motion.

- Landmark Identification: Precision is necessary. The goniometer must be aligned with specific bony landmarks. For shoulder abduction, the stationary arm is aligned with the trunk, the axis is placed at the center of the humeral head, and the moving arm follows the humerus.

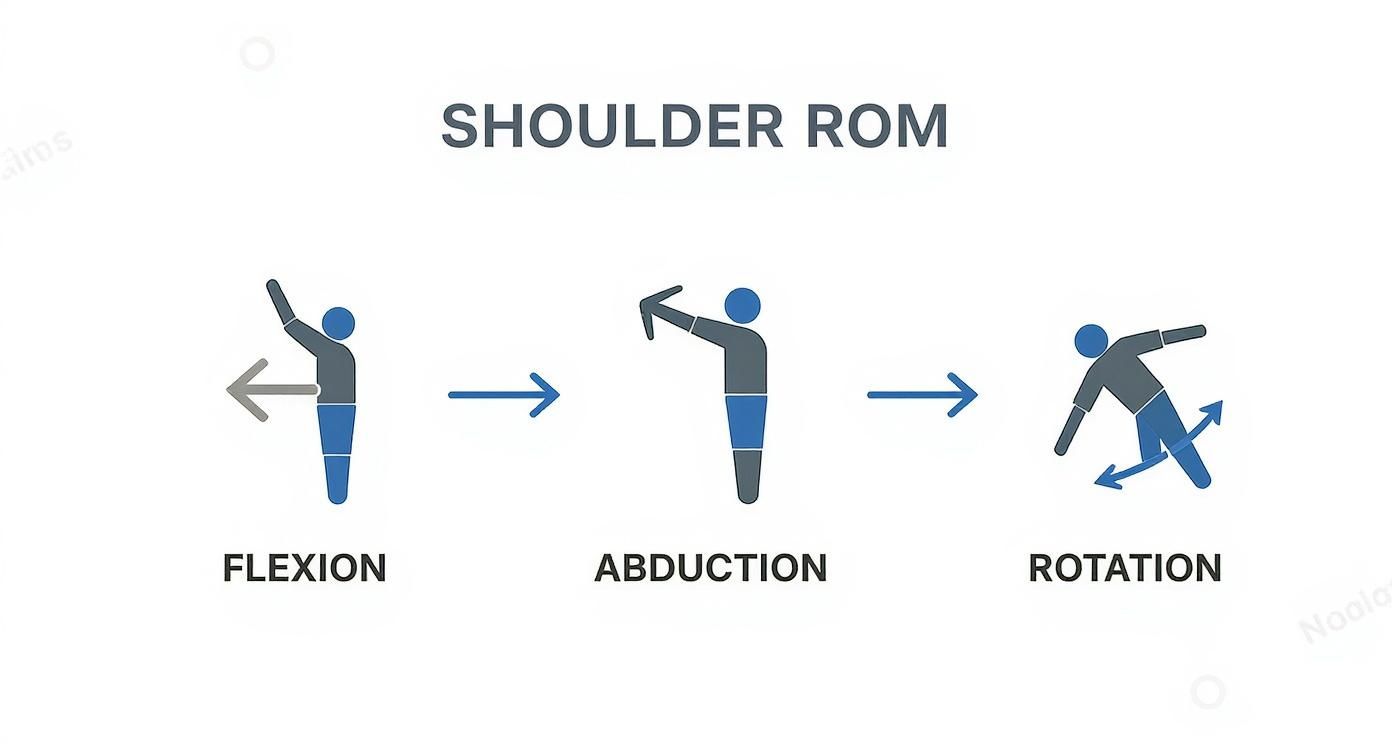

This diagram illustrates the primary movements assessed during a shoulder ROM evaluation.

As shown, flexion, abduction, and rotation each describe a unique arc of motion originating from the shoulder joint.

Modern Tools for Enhanced Precision

While the classic goniometer is a reliable instrument, modern tools can offer a new level of precision. Digital inclinometers and validated smartphone applications are increasingly used in clinical and sports performance settings. These devices provide rapid, repeatable measurements and often include features that simplify data recording and tracking over time.

Research has shown that digital tools can offer excellent intra-rater reliability, meaning a single user can obtain highly consistent results (4). However, the fundamental principles of positioning and stabilization remain just as crucial, regardless of the technology used.

Ultimately, whether using a traditional goniometer or a modern digital device, the protocol is what ensures reliable data. For a comprehensive overview of these techniques, our guide on how to measure range of motion provides further detail. Adherence to a standardized method ensures the data collected is a true reflection of the patient's joint health—a vital component for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and progress tracking.

How Age and Gender Influence Shoulder Mobility

Shoulder mobility is not a static value but a dynamic measure that naturally changes throughout a person's life. Age and gender are two of the most significant factors influencing this change. For clinicians, understanding these influences is essential for setting realistic rehabilitation goals. For individuals, it provides context for their own joint health.

Peer-reviewed studies consistently demonstrate a gradual, predictable decline in shoulder range of motion with advancing age (1, 5). This is not necessarily a sign of injury or pathology but rather a normal part of the physiological aging process. Tissues such as ligaments and the joint capsule lose some elasticity, and a natural decrease in muscle strength can further contribute to a more restricted arc of movement.

The Impact of Aging on Shoulder Function

Population data clearly shows that mobility in key planes like flexion and abduction tends to decrease with each decade of life. This pattern is observed in both men and women, although the specific rate of change may differ between the sexes.

For instance, a healthy male in his 20s might demonstrate an active flexion of approximately 160 degrees. By his 60s, that average could decrease to around 145 degrees (1). Recognizing this natural decline allows a clinician to distinguish between expected, age-related stiffness and a true limitation requiring intervention.

This progressive decline is why applying a single universal "normal" value to every patient is clinically inappropriate. A personalized approach that considers an individual's age is far more effective for accurate assessment and meaningful goal setting.

A large cohort study provides a clear snapshot of this trend, showing how active shoulder flexion and abduction change across the decades.

Mean Active Shoulder ROM by Age Group and Gender (Degrees)

This table presents normative data from a large cohort study, illustrating the decline in shoulder flexion and abduction across different age decades for males and females (1).

| Age Group (Years) | Mean Flexion - Male (°) | Mean Flexion - Female (°) | Mean Abduction - Male (°) | Mean Abduction - Female (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-29 | 160 | 165 | 170 | 175 |

| 30-39 | 155 | 160 | 165 | 170 |

| 40-49 | 150 | 155 | 160 | 165 |

| 50-59 | 148 | 152 | 155 | 160 |

| 60-69 | 145 | 148 | 150 | 155 |

The data shows a clear, gradual reduction in both planes of motion, reinforcing the need to adjust clinical benchmarks based on a patient's age.

Gender-Specific Differences in Mobility

In addition to age, gender plays a noticeable role in shoulder range of motion norms. On average, females tend to exhibit slightly greater shoulder mobility than males across most age groups, particularly in movements like flexion and abduction (1, 5). This difference is often attributed to a combination of hormonal factors, connective tissue laxity, and subtle anatomical variations.

Of course, these are general trends, and individual variability is significant. A detailed examination of shoulder ROM norms reveals a wide "healthy" range. For example, among males aged 20-24, the lowest recorded healthy flexion was 90°, while for females aged 40-44, the lowest abduction was 66° (1).

Understanding these variables is crucial for anyone assessing movement. It underscores the point that a "normal" range is not a single number but a spectrum heavily influenced by demographic factors. These age and gender patterns are similar to those observed in other functional tests. For more on this, you can read our article on sit-to-stand test norms, which also explores demographic influences on performance.

By integrating data on age and gender, we can create a much more accurate and individualized picture of what constitutes healthy shoulder motion. This informed perspective is the foundation of effective diagnosis, realistic rehabilitation goals, and successful long-term outcomes.

Active vs Passive ROM: What the Difference Reveals

When assessing shoulder range of motion, we are examining two distinct capacities: what a person can achieve through their own effort, and what their joint is structurally capable of moving. This is the crucial distinction between Active Range of Motion (AROM) and Passive Range of Motion (PROM). The relationship between these two values provides powerful diagnostic information.

AROM represents the movement a person achieves using their own muscles. PROM is the range a clinician can move the joint through with an external force. Comparing these two measurements is a fundamental step in determining the source of a limitation—whether it is a problem with the muscles and nerves (the "engine") or a structural block within the joint itself.

Interpreting the AROM vs. PROM Relationship

The clinical picture becomes clearer when we compare a patient’s active and passive movements. This simple comparison can quickly narrow the potential causes of shoulder dysfunction and focus the subsequent examination.

-

AROM is less than PROM: This is a classic indicator of a deficit in muscle strength or neuromuscular control. The joint itself is free to move (as demonstrated by the full PROM), but the patient's own musculature cannot complete the movement. This pattern points toward issues such as a rotator cuff tear, nerve impairment, or significant muscle weakness.

-

AROM and PROM are equally limited: When both active and passive motion are restricted at the same point, often accompanied by pain, a structural or mechanical issue is likely. The limitation is not due to muscle failure but rather a physical block to movement. This is a hallmark of conditions like adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) or significant osteoarthritis, where the joint capsule or surfaces prevent motion regardless of the force applied.

A key clinical takeaway is that a significant difference between AROM and PROM often suggests that the joint's structure is intact, but the muscular "engine" is failing. This directs treatment toward strengthening and motor control interventions.

Practical Diagnostic Scenarios

Consider these two real-world examples:

Scenario 1: Muscle Weakness

A patient can only actively lift their arm to 90 degrees of abduction (AROM). However, the clinician can easily and painlessly move the arm to 160 degrees (PROM).

This large gap strongly suggests a muscular deficit. The next step would be to perform specific strength assessments, such as those described in our guide on manual muscle testing procedures, to confirm a suspected rotator cuff injury.

Scenario 2: Joint Restriction

Another patient presents with a stiff, painful shoulder. They can only actively lift their arm to 100 degrees of flexion. When the clinician attempts to move the arm passively, they encounter a firm block at the same 100-degree mark.

Because AROM and PROM are equally restricted, this immediately suggests a capsular problem such as adhesive capsulitis, where the joint itself is the barrier.

By systematically comparing active and passive range of motion, we can efficiently differentiate between muscle weakness and joint restriction, leading to a more accurate diagnosis and a more effective, targeted rehabilitation strategy.

Applying Normative Data in Clinical Practice

Acquiring accurate range of motion (ROM) numbers is only the first step; clinical skill lies in their interpretation. The true value of shoulder range of motion norms is not merely to compare a patient against an average, but to use that data as a basis for deeper clinical reasoning and to develop a treatment plan tailored to the individual.

A single measurement—for instance, 140 degrees of flexion—is of little value without context. Is this a 25-year-old swimmer or a 70-year-old retiree? Is the contralateral shoulder symmetrical? Most importantly, does this limitation prevent them from performing meaningful activities, whether playing tennis or reaching into a high cabinet?

Identifying Clinically Meaningful Deviations

A deviation from the norm becomes "clinically meaningful" only when it is linked to a functional deficit or suggests a specific pathology. Minor asymmetries or values slightly below textbook standards often represent normal human variation. A significant, unexplained loss of motion, however, is a clear signal for further investigation.

For example, a notable loss of internal rotation coupled with pain during overhead movements can be a classic sign of shoulder impingement syndrome, where tendons or the bursa are compressed in the subacromial space (6). In another case, a global loss of both active and passive motion is a hallmark of adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder).

These patterns highlight why we must interpret data, not just collect it. The measurements guide our hands-on examination and help us arrive at an accurate diagnosis.

Patient Goals and Functional Context

Ultimately, the objective is not to make every patient achieve a textbook number. The goal is to restore the function they need for their specific life. A professional baseball pitcher requires a different level of external rotation than an office worker; their rehabilitation targets must reflect this reality.

This patient-centered approach requires that we:

- Understand their activities: What specific movements are essential for their job, hobbies, or daily life?

- Set functional goals: Instead of aiming for "180 degrees of abduction," a more meaningful goal might be "the ability to comfortably lift a pot onto a high shelf."

- Consider the whole person: Age, prior injuries, and overall health status all influence what constitutes a realistic and successful outcome.

A key aspect of clinical practice is distinguishing between a statistically significant change and a change that is meaningful to the patient. Concepts like the Minimal Detectable Change are invaluable for tracking true progress.

Using Minimal Detectable Change to Track Progress

When re-measuring a patient’s ROM, how can we be sure that an improvement is genuine and not simply a variation in measurement technique? This is where the Minimal Detectable Change (MDC) is applied. The MDC is a statistical value representing the smallest amount of change that can be considered a true improvement, rising above the "noise" of measurement error.

For shoulder goniometry, the MDC is often cited as being between 5 to 10 degrees, depending on the specific movement and the reliability of the protocol used (7). In practice, this means that if a patient’s flexion improves by 8 degrees, we can be confident they have made genuine progress. An improvement of only 2-3 degrees, however, likely falls within the range of normal measurement variability.

Using the MDC helps inform better clinical decisions. It prevents over-interpretation of minor fluctuations and allows us to confidently demonstrate to patients that their rehabilitation efforts are yielding measurable results.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls in ROM Assessment

Obtaining precise and reliable shoulder range of motion measurements is fundamental, yet errors are common. The quality of the data collected is directly dependent on technique, so recognizing and avoiding frequent mistakes is critical for obtaining information that is useful for diagnosis and progress tracking.

A primary pitfall is the failure to properly stabilize the scapula. When the scapula is allowed to move freely during measurement, it contributes to the arm's total movement, which can result in an artificially high reading. This can easily mask a true deficit in the glenohumeral joint, leading to an inaccurate assessment.

Without proper stabilization, one measures the motion of the entire shoulder complex rather than isolating the glenohumeral joint. Therefore, effective stabilization, whether manual or through specific patient positioning, is non-negotiable for obtaining valid data.

Ensuring Measurement Validity

Beyond scapular control, several other factors can compromise measurement quality. Overlooking these details introduces variability, making it difficult to confidently track changes over time or compare results against established norms.

Incorrect goniometer placement is another common error. The axis must be aligned with the joint's center of rotation, and the stationary and moving arms must follow specific anatomical landmarks. Even a small misalignment can alter the reading by several degrees—enough to be misinterpreted as a clinical change.

It is also crucial to watch for patient compensation. To gain extra range, a patient might unconsciously lean their trunk, arch their back, or hike their shoulder. These are classic compensatory strategies that create a false impression of mobility. A skilled clinician must identify and correct these before taking a final measurement.

"The difference between an expert and a novice assessment often lies in the subtle control of variables. Preventing compensatory movements is just as crucial as the measurement itself, as it ensures you are testing the joint, not the patient's ability to cheat the test."

A Best-Practice Checklist for Reliable Assessment

Using a systematic checklist can significantly improve the reliability and validity of measurements. It is a simple tool that reinforces best practices and helps ensure that critical steps are not missed, leading to more dependable data on shoulder range of motion norms.

Pre-Measurement Checklist:

- Consistent Patient Positioning: Always use the same position (e.g., supine on a firm table) for repeat measurements to control for postural variables.

- Clear Patient Instructions: Explain the movement clearly. Instruct the patient to move slowly and to stop at the first sign of pain or significant resistance.

- Anatomical Landmark Identification: Palpate and verify the correct bony landmarks before placing the goniometer.

- Effective Scapular Stabilization: Use manual techniques or strategic positioning to effectively isolate glenohumeral joint motion.

- Monitor for Compensation: Maintain a close watch on the trunk, pelvis, and neck for any compensatory movements during the assessment.

By consistently applying these principles, clinicians can avoid common pitfalls and collect data that is both accurate and meaningful. This level of precision is essential for setting appropriate treatment goals, making informed clinical decisions, and providing the highest standard of care.

Frequently Asked Questions About Shoulder ROM

Exploring the specifics of shoulder range of motion can raise many questions for clinicians, students, and individuals seeking to understand their own physical condition. Here are some of the most common queries, answered with clear, evidence-based explanations.

These insights are intended to bridge the gap between raw data and practical understanding in a clinical or performance setting.

Why Are My ROM Values Lower Than the 180-Degree Standard?

It is common for individuals to find that their shoulder flexion or abduction does not reach the classic 180-degree benchmark. This value should be understood as an idealised maximum rather than a true population average.

Large-scale studies indicate that the typical range for healthy adults is often between 150 and 165 degrees (1). This variance is entirely normal. Factors such as age, gender, and individual anatomy significantly influence what is normal for you. A measurement below 180 degrees is not automatically a cause for concern, particularly if it is symmetrical with the other shoulder and does not cause pain or limit daily activities.

How Much ROM Difference Between Shoulders Is Normal?

Minor asymmetry between the dominant and non-dominant shoulders is very common and typically not a cause for concern. As a general guideline, a difference of 5-10 degrees is considered within the normal range, provided there is no associated pain or functional deficit.

In specific populations, such as overhead athletes, these asymmetries are not only common but expected. For example, it is normal for a baseball pitcher to have greater external rotation and less internal rotation in their throwing arm compared to their non-throwing arm (8). The key is to know the athlete's baseline. A large discrepancy or a sudden change, however, warrants a professional evaluation.

Can I Safely Improve My Shoulder Range of Motion?

Yes, in most cases, shoulder ROM can be improved safely and effectively with a targeted program. The crucial first step is to obtain an accurate assessment from a qualified professional, such as a physical therapist, to identify the underlying reason for the limitation.

The intervention must be tailored to the cause:

- If the issue is soft tissue tightness, a specific stretching protocol may be effective.

- If weakness or poor motor control is the primary factor, the focus should be on strengthening the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizing muscles.

Beginning a program without professional guidance can be counterproductive, especially if there is an underlying pathology. A proper diagnosis and a structured, supervised program will always yield the safest and most effective results.

What Is the Most Reliable Way to Measure Shoulder ROM?

In clinical settings, the universal goniometer remains the standard instrument. Its reliability is well-established when used with standardized protocols (3, 7).

However, the instrument is only one part of the equation. Regardless of the tool used, consistent technique is the true driver of reliability. This includes:

- Consistent patient positioning for every measurement.

- Proper stabilization of the scapula to prevent compensation.

- Accurate identification of the same anatomical landmarks for each measurement.

While newer technologies like digital inclinometers and validated smartphone apps demonstrate high reliability (4), they do not replace the need for fundamental best practices. These tools still depend on a meticulous and standardized protocol to deliver trustworthy data.

At Meloq, we believe objective data is the bedrock of better clinical decisions. Our digital measurement tools, like the EasyAngle digital goniometer, are built to help professionals capture accurate, repeatable data with ease. This ensures every assessment you make is built on a foundation of precision.

See how you can elevate your practice by visiting https://www.meloqdevices.com.