Sit to Stand Test Norms Your Functional Strength Guide

Team Meloq

Author

What if you could get a quick, reliable snapshot of your body's functional engine—specifically, the strength and endurance packed into your legs? That's where sit-to-stand test norms come in. This simple assessment provides a powerful benchmark, showing you how your performance stacks up against others in your age group and flagging potential areas that may need improvement.

Decoding Your Functional Strength

The Sit-to-Stand (STS) test is a brilliantly straightforward tool used widely by physiotherapists, sports rehabilitation specialists, and performance coaches. It may not be fancy, but it offers incredible insight into lower body strength, balance, and muscular endurance.

At its heart, the test measures something you do dozens of times a day without a second thought: getting up from a chair.

The real value emerges when we compare a score to established sit-to-stand test norms. Think of these norms as a reference map. They show us exactly how your functional strength compares to your peers, providing objective data needed to monitor progress in a conditioning program or gauge recovery from an injury.

Why This Simple Movement Matters So Much

On a fundamental level, the STS test assesses your ability to generate power from your legs and core to lift your body weight against gravity. This is an essential skill for independence and daily life, from getting out of a car to climbing a flight of stairs.

The test's simplicity is its greatest strength. It requires no complex equipment, making it a universally accessible method for gathering valuable data on functional mobility and strength (1).

Two main versions of the test are commonly used, and each tells a slightly different story about physical capabilities:

- The 30-Second STS Test: This version focuses on muscular endurance, counting how many full sit-to-stands can be completed in 30 seconds.

- The Five-Repetition STS Test (5R-STS): This version shifts the focus to power and speed, timing how quickly an individual can complete five full stands.

What the Numbers Tell Us About Aging

It is well-established that physical abilities can change with age, and the STS test is particularly effective at tracking these shifts. Research consistently shows a predictable pattern in performance across different age groups.

The 30-Second Sit-to-Stand Test (30STS) is especially useful here. For instance, normative data indicates that women aged 60-64 typically complete between 12 to 17 repetitions. A decade later, women aged 70-74 usually perform between 10 to 15 repetitions (1).

This expected decline is why the test is so valuable—it can help spot functional decline early, offering a chance to intervene before it may become a larger problem.

Performing the Test for Accurate Results

To get a reliable score—one that can be confidently compared against sit to stand test norms—the test must be performed with precision. Following a standardized protocol is essential for trustworthy results.

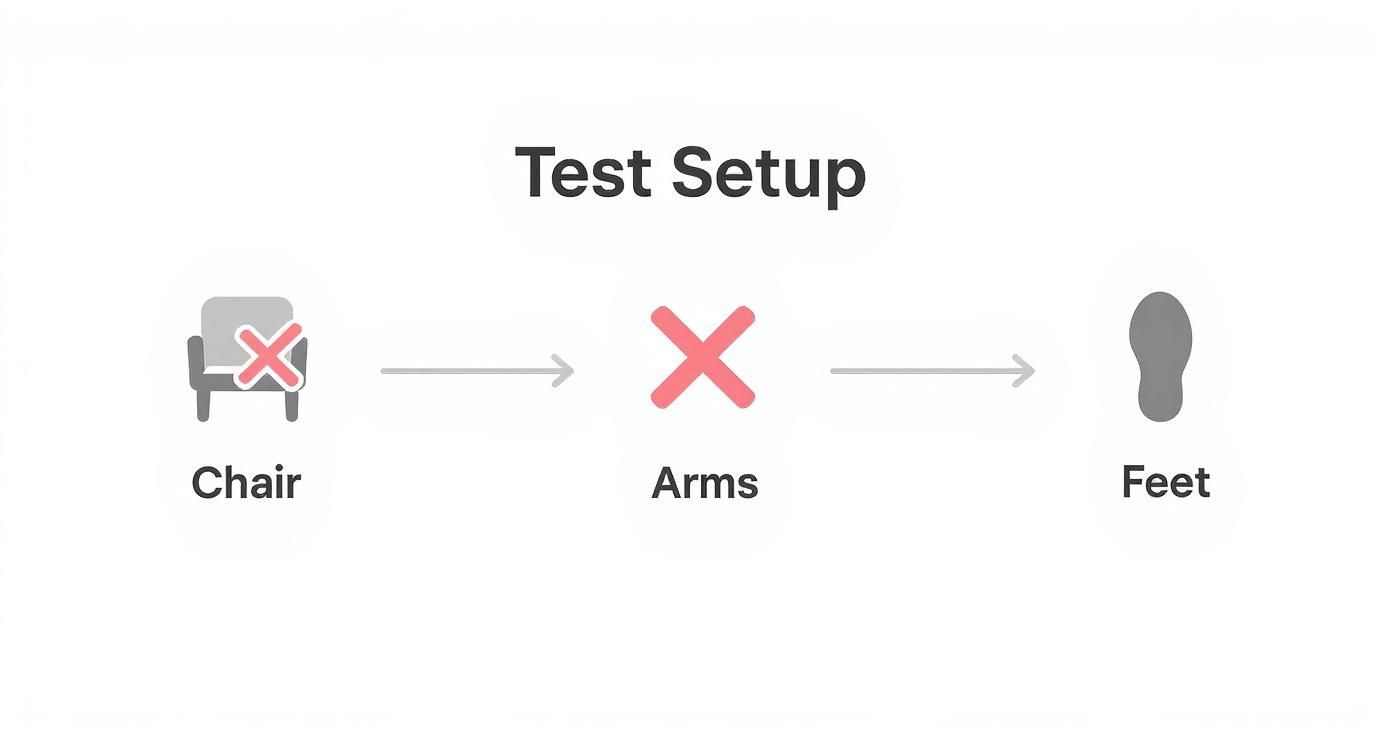

The first step is setting up the environment correctly. A consistent setup ensures that performance is a true measure of lower body strength, not something skewed by external factors. This consistency allows for meaningful comparisons over time.

The Standard Setup

To start, you need a standard, armless chair with a firm seat. The seat height is key, with an ideal range between 43 and 45 centimeters (about 17 inches) from the floor (2). This specific height is crucial because a chair that is too low or too high can dramatically change the difficulty of the movement.

Once you have the right chair, body position is next. Sit in the middle of the seat. Place your feet flat on the floor, about shoulder-width apart. Then, cross your arms over your chest so your hands are resting on the opposite shoulders.

This arm position is non-negotiable. Its purpose is to isolate the lower body muscles, preventing the use of arms to push off the legs or chair for extra momentum.

Executing the Test Variations

With the setup locked in, you're ready to perform one of the two main versions of the test. The choice usually depends on what you're trying to measure—endurance or functional power.

1. The 30-Second Sit-to-Stand Test (30STS)

This version assesses muscular endurance. The goal is to complete as many full sit-to-stand repetitions as possible in 30 seconds.

- On the "Go" command, stand up to a full, upright position.

- Immediately sit back down in a controlled manner.

- Repeat this cycle as many times as possible before the 30 seconds are up.

- A repetition only counts if you stand up completely and your bottom touches the chair when you sit back down.

2. The Five-Repetition Sit-to-Stand Test (5R-STS)

This test zeros in on functional power and speed. Here, the time it takes to complete exactly five repetitions is measured.

- The timer starts on "Go" as you begin to rise from the chair.

- Perform five full repetitions as quickly as possible without sacrificing form.

- The timer stops the moment your bottom touches the seat after the fifth and final repetition (2).

Avoiding common mistakes is critical for a valid measurement. Any repetition where hands are used, full standing position is not reached, or balance is lost should not be counted. Proper technique is the tool for accuracy, much like the precision needed in other clinical evaluations, such as those discussed in our guide to range of motion measurement tools.

Interpreting Your Score with Normative Data

Once you have your number—either the repetitions completed in 30 seconds or the time taken for five stands—the next step is interpretation. What does that score actually mean? This is where sit to stand test norms turn a raw score into useful information by showing how you compare to your peers.

Think of these norms as a reference map for functional strength. They are benchmarks, gathered from scientific studies, that show the average performance for people in specific age groups and genders. By finding your score on this map, you get a clearer picture of your lower body strength and endurance.

This infographic is a great visual reminder of the proper test setup. Sticking to the protocol is non-negotiable if you want your results to be comparable to the established norms.

The key takeaway? Standardization is everything. Using that armless chair, crossing your arms, and keeping your feet flat on the floor ensures your score can be accurately interpreted against the data.

Making Sense of the Numbers

Let's put this into a real-world context. Suppose a 68-year-old woman completes 14 stands in the 30-Second Sit-to-Stand Test. According to published data, the typical range for women aged 65-69 is between 11 and 16 repetitions (3). Her score places her in the middle of this range, suggesting a functional strength level that is average for her age.

Now, consider a 72-year-old man who takes 16 seconds to complete the Five-Repetition Sit-to-Stand Test. The expected average for his age group is around 12.6 seconds (4), so his time is slightly slower. This is not a diagnosis, but it does highlight a potential area for improving functional power and balance.

It's crucial to remember that these norms are simply reference points, not a final judgment on health. They offer valuable insight but should always be considered alongside overall health, activity level, and personal fitness goals.

Why Specific Norms Matter

Normative values are not one-size-fits-all; they can shift based on age, gender, and the population being studied. One large analysis of 45,470 participants from 14 countries found that men aged 55-59 performing the Five-Times Sit-to-Stand Test had scores ranging from 18 seconds (5th percentile) to just 5 seconds (95th percentile), with an average of 9 seconds (5).

This wide range highlights why using age- and population-specific data is vital for an accurate interpretation of performance.

A Practical Table of Normative Values

To provide a clearer picture, this simplified table summarizes average sit-to-stand norms for community-dwelling adults, based on published research (3, 4). It shows average performance scores for different age groups.

Sit to Stand Test Normative Values by Age and Gender

| Age Group (Years) | Gender | Average 30STS Repetitions (Range) | Average 5R-STS Time (Seconds) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 60-64 | Male | 14-19 | ≤ 11.4 |

| 60-64 | Female | 12-17 | ≤ 11.4 |

| 70-74 | Male | 12-17 | ≤ 12.6 |

| 70-74 | Female | 10-15 | ≤ 12.6 |

| 80-84 | Male | 9-14 | ≤ 14.8 |

| 80-84 | Female | 8-13 | ≤ 14.8 |

If a score falls below the average for an age group, it can be seen as an objective signal that focusing on lower body strength and power could make a meaningful difference in daily life and long-term mobility.

For those who want to get even more precise with training, pairing the STS test with a dynamometer for muscle testing can provide quantitative data to track strength gains over time.

Understanding Different Versions of the Test

While the basic movement is always the same—sit, stand, repeat—the sit-to-stand test is not a one-size-fits-all tool. Clinicians typically rely on two main variations: the 30-Second Sit-to-Stand Test (30STS) and the Five-Repetition Sit-to-Stand Test (5R-STS).

Each one provides slightly different information about a person's physical function. Understanding why a professional might choose one over the other depends on the specific question they are trying to answer.

The 30-Second Test: A Measure of Endurance

The 30STS can be thought of as a muscular endurance sprint. The objective is to complete as many repetitions as possible within a 30-second window. This makes it a great tool for gauging functional fitness in more active individuals or for tracking progress in a conditioning program.

A physiotherapist might use the 30STS to monitor an athlete's lower body stamina during their season or to assess a healthy older adult's capacity for sustained activity. It directly answers the question: "How much work can your legs do in a short burst?"

The number of repetitions achieved in 30 seconds provides a clear metric for lower body power-endurance, a crucial component for everyday activities like climbing stairs, walking briskly, or playing recreational sports.

Because it demands constant effort for a set time, the 30STS can be taxing. For some individuals, a quicker, more power-focused alternative may be a better fit.

The Five-Repetition Test: A Snapshot of Power

In contrast, the 5R-STS focuses on speed and functional power. The time it takes to complete exactly five repetitions is measured. It’s a quick and effective snapshot of an individual's ability to generate the force needed to stand up efficiently.

This version is often used in clinical settings, especially for individuals who might find the 30-second test too demanding, such as someone recovering from surgery or an older adult with significant deconditioning. It is less about endurance and more about the fundamental ability to perform the movement itself.

The 5R-STS is also a valuable tool for assessing function in diverse populations. For instance, its simplicity makes it accessible for individuals with intellectual disabilities. One study found that adolescents with intellectual disabilities completed the test in about 6.55 to 7.24 seconds, showing its utility as a quick and effective assessment in this group. You can explore this research in the full study (6).

How Professionals Use Sit to Stand Test Scores

A Sit to Stand test score is more than just a number. For health and performance professionals, it's a critical piece of information used to build effective, personalized programs. The applications are surprisingly broad, ranging from geriatric care to elite sports conditioning.

One of its most important uses is in fall risk assessment for older adults. Research indicates a correlation between lower sit-to-stand scores and a higher chance of falling (7). A slower time or fewer repetitions can be a red flag, signaling potential deficits in lower body strength, power, and balance—all essential for stability.

From Rehabilitation to Peak Performance

In a clinical setting, this test is an invaluable yardstick for recovery. For someone recovering from a knee or hip replacement, a therapist can use the STS test to objectively track progress. Seeing the five-repetition time decrease from 20 seconds to 15 seconds over a few weeks is concrete proof that the rehabilitation plan is effective.

This score can be a powerful motivator for the patient and provides the clinician with hard data to adjust exercises and advance the program.

By comparing a patient's score to established sit to stand test norms, a therapist can set realistic, evidence-based goals. It helps answer the question, "What does a successful recovery look like for someone in this age group?"

The test's utility extends into sports conditioning, where lower body power and endurance are paramount. Coaches use different versions of the sit-to-stand test to:

- Monitor muscular endurance: The 30-Second test is a useful way to gauge an athlete's leg stamina throughout a long season.

- Assess functional power: A fast time on the Five-Repetition test indicates an athlete can generate force quickly—a key attribute for jumping, sprinting, and changing direction.

- Establish a baseline: A pre-season score provides a crucial benchmark. If an injury occurs, there is a clear target to aim for before a safe return to play.

Ultimately, the test score informs the training plan. For an older adult, a low score might lead to a program emphasizing leg presses and balance work. For an athlete, it could mean adding plyometrics and explosive squats. The number is just the starting point; its true value is in guiding the next steps.

Common Questions About the Sit to Stand Test

Even with a clear understanding of protocols and norms, practical questions often arise when using the sit-to-stand test. Here are straightforward answers to some of the most common inquiries from clinicians and patients.

What if I Need to Use My Hands to Stand Up?

Using hands to push off the knees or a chair is a critical observation, not a "failure." It signals that the lower body may not yet have the strength to lift body weight independently. In a formal test, any repetition where hands are used does not count toward the final score (8).

If this happens during a self-assessment, it's a cue to focus on foundational strengthening. A physiotherapist can design a safe, progressive program with exercises like assisted chair squats or leg presses to build the necessary strength.

How Often Should I Retest to Track Progress?

To see meaningful changes, retesting every 4 to 6 weeks is a good cadence. This provides enough time for the body to adapt to a new training program, allowing strength gains to become measurable.

Testing too frequently, such as weekly, may not show significant change and could be discouraging. A therapist or coach can help set a retesting schedule that aligns with specific rehabilitation or performance goals.

Is It Possible to Improve My Sit to Stand Score?

Absolutely. A sit-to-stand score is highly trainable. As a direct reflection of lower body strength and power, it can be improved with a consistent training program targeting the appropriate muscle groups.

A better score isn't just a number—it translates directly to improved functional mobility. Everyday tasks like getting out of a car, climbing stairs, or rising from a low sofa may feel easier and more stable.

To boost performance, focus on exercises that mimic the sit-to-stand motion and build overall leg strength. Consider adding these to your routine:

- Bodyweight Squats: This is the most direct way to practice the movement pattern.

- Lunges: Great for building single-leg strength and challenging balance.

- Step-Ups: Excellent for developing power in the glutes and quads.

- Glute Bridges: These target the posterior chain, which is crucial for the "lift-off" phase of standing.

By improving strength, you are investing in long-term independence and physical capability. To learn more about building this type of functional power, check out our guide to dynamic strength exercises.

When Should I Avoid Performing This Test?

Safety is always the priority. The sit-to-stand test should not be performed if you are experiencing acute pain in your back, hips, or knees. The same applies if you have recently had lower body surgery and have not been cleared by your surgeon or physiotherapist.

It is also wise to avoid the test if you have severe balance issues, a history of recent falls, or a medical condition that causes dizziness with exertion. When in doubt, always consult a healthcare professional before beginning.

References

- Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Development and validation of a functional fitness test for community-residing older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 1999;7(2):129-161.

- Goldberg A, Chavis M, Watkins J, Wilson T. The five-times-sit-to-stand test: validity, reliability and detectable change in older females. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24(4):339-344.

- Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Beam WC. A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70(2):113-119.

- Bohannon RW. Reference values for the five-repetition sit-to-stand test: a descriptive meta-analysis of data from elders. Percept Mot Skills. 2006;103(1):215-222.

- Strassdorn U, Dworak M, V. Wilm S, D. Schwenk M, Schmidt T. The five-times-sit-to-stand test (FTSST) in an international adult population: a systematic review and meta-analysis of normative reference values. Sports Med. 2021;51(10):2181-2195.

- García-Soidán JL, Leirós-Rodríguez R, Romo-Pérez V, García-Liñeira J. Sit-to-stand test in adolescents with intellectual disability: a reliability and concurrent validity study. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2019;63(7):858-866.

- Buatois S, Perret-Guillaume C, Gueguen R, Miget P, Vançon G, Perrin P, Benetos A. A simple clinical scale to stratify risk of falling in community-dwelling older adults. Phys Ther. 2010;90(4):550-560.

- Whitney SL, Wrisley DM, Marchetti GF, Gee MA, Redfern MS, Furman JM. Clinical measurement of sit-to-stand performance in people with balance disorders: validity of data for the five-times-sit-to-stand test. Phys Ther. 2005;85(10):1034-1045.

At Meloq, we believe that objective data is the key to unlocking better outcomes. Our ecosystem of digital measurement tools, including the EasyForce dynamometer and EasyAngle goniometer, empowers professionals to move beyond subjective assessments and capture the precise data needed to build effective, evidence-based programs. See how our devices can bring clarity and accuracy to your practice by visiting https://www.meloqdevices.com.