What Is Center of Pressure? A Guide to Balance and Rehabilitation

Team Meloq

Author

The center of pressure (COP) represents the single point on a surface where the total sum of all pressure acts. In human movement, this is the point beneath the feet where the ground reaction force is applied (1). It is an invaluable, objective window into how an individual maintains their balance.

Understanding What Center of Pressure Reveals

Even during quiet standing, the human body is not perfectly motionless. It undergoes continuous, subtle postural adjustments to maintain an upright stance, a phenomenon known as postural sway (2). These micro-movements cause constant shifts in how body weight is distributed across the ground. The center of pressure is the precise location tracking the average of all these pressures from moment to moment.

In physiotherapy and sports science, the COP is where the ground reaction force (GRF) is concentrated. Observing how this point moves allows clinicians to objectively measure how well an individual's neuromuscular system is controlling their posture and stability. For a deeper scientific background, you can explore the foundations of COP on Physio-pedia).

This data provides a direct, unfiltered look into a person's balance strategies, moving assessments far beyond subjective observation into the realm of quantitative analysis.

Why It Matters in a Clinical Setting

Quantifying the center of pressure is transformative for clinical practice. It turns a subjective observation, such as "the patient seems unsteady," into a concrete, objective measurement like, "the patient's sway area has increased by 30% compared to their baseline."

This data-driven approach is fundamental for tracking progress, assessing fall risk, and designing rehabilitation programs that target specific neuromuscular deficits (3).

By analyzing COP movement patterns, clinicians can pinpoint specific issues in postural control that might otherwise be missed. This insight leads directly to more effective, evidence-based interventions for a wide range of patient populations.

The following table breaks down the core concepts behind the center of pressure.

Center of Pressure at a Glance

| Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| What It Is | The point of application of the total ground reaction force, representing the body's moment-to-moment balance point. |

| Why It Matters | It provides an objective, quantifiable measure of postural stability, balance control, and neuromuscular function. |

| Who Benefits | Patients in neurological or orthopedic rehabilitation, older adults at risk of falls, and athletes optimizing performance or returning to play. |

This summary illustrates how a seemingly simple biomechanical metric can have a profound impact, whether working with an older adult to regain functional independence or an elite athlete fine-tuning their stability.

The Relationship Between Center of Pressure and Center of Mass

To fully understand the center of pressure, it is essential to discuss its relationship with the center of mass (COM).

The COM is the body's theoretical balance point—the average location of all its mass. While the COM is an internal point, the COP is the external point of force application on the ground. The COP's movement is the physical result of the neuromuscular system constantly working to keep the COM within the base of support.

The two are intrinsically linked in a dynamic relationship. The primary goal of the postural control system is to keep the vertical projection of the COM within the boundaries of the base of support (the area covered by the feet). To achieve this, the nervous system continuously modulates muscle activity. These adjustments shift the COP, which in turn creates a corrective torque, or rotational force, on the body (2).

This constant, subtle corrective action is the essence of maintaining balance. If the COM begins to drift, the COP is shifted to generate the necessary torque to guide the COM back toward a stable position.

The Dynamics of Postural Sway

This continuous, minute movement of the center of pressure around the center of mass is called postural sway. It is not a sign of instability but rather the hallmark of a healthy, active balance control system. The brain constantly integrates sensory information and makes fine motor adjustments, and the movement of the COP is the observable output of this complex feedback loop.

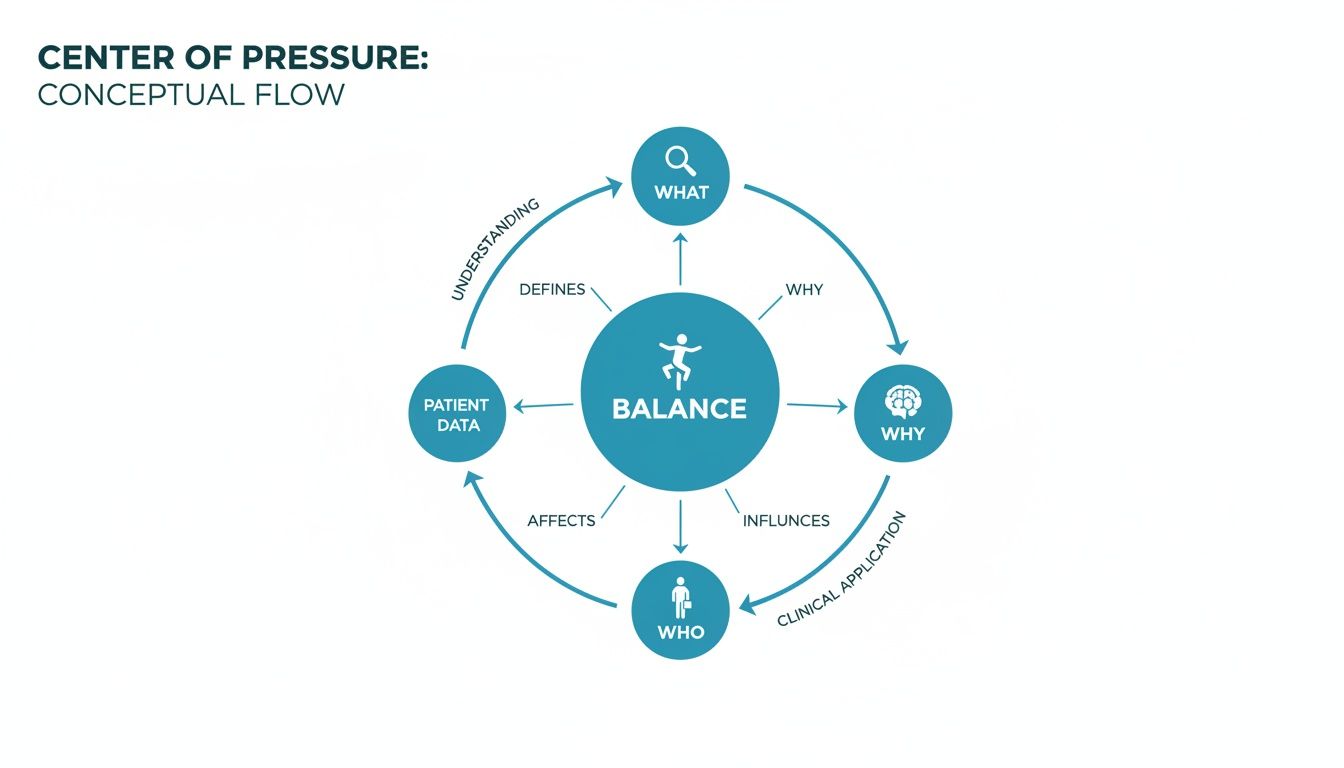

This conceptual map shows how balance is fundamentally an interplay between what the COP is, why it is measured, and who benefits from the data.

As the visual illustrates, understanding the center of pressure is fundamental to assessing and improving human balance in both clinical and athletic contexts.

A core concept in biomechanics is that the COP must move more than the COM to maintain control. If the COP's movement is too slow or its excursion is insufficient, the COM can drift outside the base of support, leading to a loss of balance (2).

A key takeaway for clinicians is that the COP is not just a point, but a controller. Its movement directly influences the stability of the center of mass. Analyzing the characteristics of this movement—how fast it moves, how far it travels—provides deep insight into the effectiveness of a person’s balance strategy.

Understanding this relationship is crucial for interpreting why certain COP patterns emerge. A large, erratic COP path is not random noise; it may signal a less efficient control strategy, suggesting the body is expending excessive energy to keep the COM stable. Conversely, a very small, controlled sway pattern often indicates a highly refined and efficient neuromuscular system.

How We Measure Center of Pressure and Key Metrics

To transform the abstract concept of the center of pressure into a tangible, measurable variable, specialized equipment is required. The gold standard for measuring COP is the force plate, a tool that acts as a highly sensitive multi-axis scale.

Force plates contain multiple sensors that detect both the magnitude of the applied force and its precise location. When an individual stands on the plate, these sensors measure the ground reaction forces in real time. Software then calculates the exact coordinates of the COP from one millisecond to the next. You can learn more about how force platforms are used in biomechanics in various applications.

This process generates a continuous stream of data, which is then translated into standardized metrics that provide a clear narrative about an individual's postural control and balance strategy.

Translating Raw Data into Clinical Insights

A force plate generates a visual plot of the COP's trajectory over a set time period, typically 30 seconds. This plot is known as a stabilogram, and it is from this path that clinically meaningful metrics are derived.

These metrics provide an objective language to describe stability, moving beyond simple qualitative observation.

Common COP Metrics and Their Clinical Meaning

By analyzing the characteristics of the COP's movement, different aspects of postural control can be quantified. Below are some of the most common metrics used in clinical practice and research, along with their interpretation.

| Metric | What It Measures | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Sway Area | The total area enclosed by the COP's path during a test. | A larger area suggests a greater displacement of the COP is required to maintain balance, potentially indicating less efficient control and an increased risk of instability (4). |

| Path Length | The total distance the COP travels over the test period. | A longer path implies more frequent corrective movements were needed, often signaling a less refined or more reactive balance strategy (4). |

| Sway Velocity | The average speed of the COP's movement (Path Length / time). | Higher sway velocity is strongly associated with poorer postural control, reflecting the need for rapid, constant adjustments to avoid losing balance (5). |

These three metrics alone provide a powerful snapshot of an individual's stability.

For example, a patient recovering from an ankle sprain might show a week-over-week reduction in sway area and velocity during rehabilitation. This is not merely a subjective feeling of improvement; it is objective proof that their neuromuscular control is being restored. This is how assessment moves from observation to precise, evidence-based practice.

Interpreting COP Data for Fall Risk and Gait Analysis

Once a force plate captures the center of pressure data, the real clinical work of interpretation begins. This stream of quantitative data provides a direct window into the performance of a patient's neuromuscular control system. Learning to interpret this information is key to identifying balance deficits, detecting subtle gait asymmetries, and assessing fall risk, particularly in older adults and individuals with neurological conditions.

When raw data is transformed into actionable insights, we can move from simply measuring balance to truly understanding it. For instance, a patient might appear steady to the naked eye, but their COP data could reveal a high sway velocity. This indicates their body is working excessively, making rapid and potentially fatiguing adjustments to stay upright—an early warning sign that might otherwise be missed.

From Numbers to Neuromuscular Narratives

Think of COP metrics as the vocabulary describing a person's balance story. A large sway area often points to a less efficient postural control strategy, while a long path length suggests a high frequency of corrective actions to maintain equilibrium.

These numbers help clinicians investigate the why behind a stability problem. Is the deficit due to delayed reaction time, an inability to make fine adjustments, or muscular weakness? The data provides clues needed to construct a more targeted and effective rehabilitation plan.

Interpreting center of pressure data is less about finding a single "bad" number and more about understanding the overall pattern of control. Significant deviations from established normative values often signal underlying stability issues that warrant deeper clinical investigation.

Tracking a patient's data against their own baseline creates a powerful, objective timeline of their progress. This is empowering for both the clinician and the patient, offering clear evidence of improvement or highlighting areas that require further attention. To see how this fits into a broader movement assessment, you can explore the principles of a gait analysis using force plates.

Identifying and Predicting Fall Risk

One of the most impactful applications of COP analysis is in the prediction and prevention of falls, a major concern for older adults. Scientific literature provides strong evidence linking specific COP metrics to fall risk. Increased sway area, for instance, is a well-established biomarker for a higher likelihood of falls (3, 5).

Studies have shown clear differences in postural sway between age groups. One comprehensive review found that while healthy young adults typically exhibit a sway area of around 0.4 cm², individuals over 70 can show an average sway area of 1.2 cm² (6). This threefold increase signals a significant decline in postural stability. You can discover more insights about Center of Pressure findings on Physio-pedia). This type of objective data is crucial for identifying at-risk individuals before a fall occurs.

Ultimately, by understanding what the center of pressure is and how to interpret its subtle movements, physiotherapists can design more intelligent, evidence-based interventions. This data-driven approach not only improves patient outcomes but also provides the objective documentation needed to validate treatment plans and demonstrate measurable functional gains.

Applications in Sports Rehabilitation and Performance

Applying center of pressure analysis in an athletic setting provides a powerful, objective lens through which to view movement. It allows coaches and rehabilitation specialists to see what the naked eye cannot, uncovering subtle inefficiencies and asymmetries that may limit performance or, more critically, increase injury risk. This data is invaluable for making informed decisions regarding training loads, technique modifications, and return-to-play protocols.

By quantifying an athlete's stability, we can design programs that are far more precise and effective. Consider an athlete recovering from an ACL reconstruction. A primary goal of their rehabilitation is restoring symmetrical balance and control. Tracking their COP metrics, such as sway velocity on the injured leg versus the uninjured leg, provides objective evidence of neuromuscular recovery. It helps determine when they are truly ready for the dynamic demands of their sport.

Identifying Injury Risks Before They Happen

A promising application of COP analysis is in the prospective screening for injury risk. Many non-contact injuries, such as ankle sprains, are linked to deficits in neuromuscular control during dynamic movements like landing from a jump or cutting (7). By measuring an athlete’s center of pressure during such tasks, hazardous movement patterns that are invisible in real-time can be identified.

For example, when an athlete lands from a jump, their COP should be controlled smoothly and symmetrically. Research on jump-landing tasks has shown that significant medial or lateral shifts in the COP upon landing are associated with an increased risk for lower extremity injuries (8). This insight allows practitioners to intervene with targeted stability training to correct the issue before it leads to time lost from competition. If you want to dive deeper into this topic, our guide on balance training for athletes is a great resource.

For performance professionals, the center of pressure is not just a measure of balance—it's a proxy for neuromuscular efficiency. A stable and controlled COP trace during a dynamic task indicates that an athlete is generating and absorbing force effectively, which is the foundation of high-level performance.

Bringing Lab-Grade Data to the Training Ground

Not long ago, this level of biomechanical analysis was confined to research laboratories. However, the development of modern, portable force plates has brought this technology directly to the sidelines and into the strength and conditioning facility.

This accessibility has significant implications for practice:

- Immediate Feedback: Coaches can analyze an athlete's landing mechanics or single-leg stability and provide real-time cues based on objective data.

- Routine Monitoring: Regular COP assessments can be used to track an athlete's neuromuscular fatigue over a competitive season, helping to manage training loads and mitigate overuse injuries.

- Optimized Technique: In sports demanding rotational power, like golf or baseball, the COP path reveals how an athlete transfers energy from the ground up, highlighting opportunities to refine technique for greater power generation.

Ensuring Your COP Measurements are Accurate and Reliable

The quality of your clinical insights depends directly on the quality of your data. To ensure that your center of pressure measurements are both accurate and reliable, establishing a standardized protocol is essential. This is critical for tracking a patient's progress over time and providing effective, evidence-based care.

Consistency is paramount. Every detail, from the phrasing of instructions to the testing environment, can influence the results. Small inconsistencies introduce variability into the data, making it difficult to distinguish between genuine clinical change and measurement error.

Key Protocol Considerations

To capture clean, trustworthy data, the primary goal is to standardize the entire assessment process. This creates a stable baseline from which to track genuine progress.

- Standardize Your Instructions: Use the exact same verbal cues for every test. Simple, clear instructions like, "Stand as still as you can, looking straight ahead," promote consistency.

- Set Consistent Test Durations: A 30-second trial is a widely accepted standard in research and clinical practice. This duration is sufficient to obtain reliable data without inducing significant patient fatigue (2).

- Keep the Environment Stable: Conduct tests in a quiet area, free from distractions. A calm setting helps the patient focus, ensuring the data is an accurate reflection of their intrinsic postural control.

Common Pitfalls to Sidestep

Even with a robust protocol, subtle errors can compromise data quality. Awareness of common pitfalls is the first step toward avoiding them.

One of the most common errors is inconsistent foot placement. Even a slight change in stance width or foot angle between sessions alters the base of support. This significantly affects COP metrics and invalidates comparisons across different testing sessions.

Furthermore, be mindful of patient distractions. Allowing conversation or visual scanning during a test introduces external variables that disrupt natural postural sway. For clinicians wanting to delve deeper into equipment considerations, our guide on choosing a device to measure force offers valuable context. By controlling these factors, you can be confident that the data reflects your patient’s ability, not the testing environment.

Common Questions About Center of Pressure

When clinicians and coaches first incorporate center of pressure analysis, several practical questions often arise. Here we address some of the most common queries regarding testing, technology, and data interpretation.

How Long Should a Standard Static Balance Test Last?

While protocols can vary, a 30-second trial is widely considered the standard for a reliable static balance assessment.

Foundational research indicates this duration provides a stable representation of postural sway. It is long enough to capture key metrics like sway area and velocity, but brief enough to minimize the confounding effects of fatigue (2).

Do I Need an Expensive Lab to Measure COP?

No, this is a common misconception. High-fidelity biomechanical analysis is no longer confined to university research laboratories.

Modern portable force plates are designed specifically for clinical and field use. They provide medical-grade accuracy for essential COP metrics, making objective balance assessment feasible for private practices, rehabilitation centers, and sports teams.

What's the Difference Between a Single-Leg and Double-Leg COP Test?

A double-leg stance test assesses overall postural stability with a wide, stable base of support. It is an excellent tool for general balance screening and evaluating fall risk in various populations.

In contrast, a single-leg stance test significantly increases the challenge to the postural control system. It isolates one limb to assess unilateral stability, proprioception, and neuromuscular control. This makes it an invaluable test in post-injury rehabilitation—such as after an ankle sprain or ACL surgery—to identify asymmetries and monitor recovery progress.

At Meloq, our focus is on creating precise, portable measurement tools that help you swap subjective guesswork for objective data. See for yourself how our force plates can deliver actionable insights for your clinic or team. You can learn more about our tools on the Meloq website.

References

- Winter DA. Human balance and posture control during standing and walking. Gait & Posture. 1995;3(4):193-214.

- Duarte M, Freitas SM. Revision of posturography based on force plate for balance evaluation. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy. 2010;14(3):183-92.

- Piirtola M, Jäntti P. Use of force platform in balance assessment of the elderly. Gerontology. 2009;55(2):227-32.

- Prieto TE, Myklebust JB, Hoffmann RG, Lovett EG, Myklebust BM. Measures of postural steadiness: differences between healthy young and elderly adults. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 1996;43(9):956-66.

- Maki BE, Holliday PJ, Topper AK. A prospective study of postural balance and risk of falling in an ambulatory and independent elderly population. Journals of Gerontology. 1994;49(2):M72-84.

- Błaszczyk JW. The use of posturography in the diagnosis of stability disorders. In: Biomedical Engineering. IntechOpen; 2011.

- Hrysomallis C. Relationship between balance ability, training and sports injury risk. Sports Medicine. 2007;37(6):547-56.

- Sell TC, Ferris CM, Abt JP, et al. Predictors of proximal tibia anterior shear force during a vertical stop-jump. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2007;37(10):593-600.